|

Diarrhea, weight loss and fatigue in a heart transplant recipient |

- History of Present Illness

- A woman in her 50s with a history of heart transplant (CMV D-/R+, EBV D-/R+, toxo D-/R-) about two years prior to presentation was admitted to the hospital with three months of diarrhea, fatigue, cognitive slowing, and weight loss. She also had one week of anorexia with shortness of breath and congestion, and one day of fevers. The patient denied cough, urinary symptoms, and abdominal pain.

- Past Medical History

- Heart transplant due to non-ischemic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, thought to be due to viral myocarditis in the past.

- Listeria brain abscess, one month following transplant, initially treated with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) for 4 months, and then with TMP-SMX alone for 2 additional months. The patient then took suppressive TMP-SMX for 6 months (12 months of therapy total). The patient had stopped TMP-SMX about a year prior to the current presentation.

- Allergic to TMP-SMX with a history of rash, convulsions as a child. The patient had been desensitized to TMP-SMX before receiving it for treatment of Listeria. She had stopped TMP-SMX about a year prior to the current presentation.

- One prior episode of rejection, approximately one year ago, treated with pulse dose steroids.

- Epidemiological History

- Born in South America; she had pre-transplant travel to Asia.

- Post-transplant travel included Southern California, recent camping in the Midwest.

- Dog and a cat at home. The patient was in contact with new cats around one month prior to presentation.

- Physical Examination

- Hemodynamically stable, fatigued and cachectic but in no acute distress. Alert and oriented x3 although slow to respond, without focal neurologic abnormalities. Cardiac exam regular rate and rhythm without murmur, no edema. Breathing comfortably on room air, lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. A retinal exam conducted by Ophthalmology was normal.

- Studies

WBC 8.6 x 103 cells/µL (eosinophils 2440 cells/µL, lymphocytes 840 cell/µL) Na 130 mmol/L, AST 137 U/L, ALT 57 U/L, CRP 42 mg/L, LDH 1112 U/L, pro-BNP 31,097 pg/mL (normal range <125). hsTrop 16,740 ng/L (normal range <14) initially; troponin peaked at 20,150 before down-trending to 17,000. Total IgG 370 mg/dL. Two blood cultures on admission were negative for growth, urine culture negative, multiplex respiratory viral nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) panel negative, CMV and EBV NAAT serum negative, stool multiplex gastrointestinal pathogen panel by NAAT notable only for Enteropathogenic E. coli.

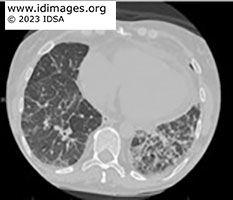

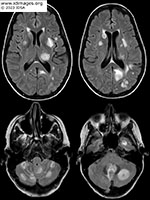

CT chest showed upper lobe fine pulmonary nodules, multifocal subsolid and groundglass nodules throughout, with more dense ground glass opacities in the lower lobes. CT abdomen and pelvis did not show evidence of enterocolitis or cholecystitis. MRI brain demonstrated extensive supra- and infratentorial ring enhancing brain lesions consistent with abscesses, some of which were present in the deep grey nuclei.

- Figure 1a. CT scan of chest without contrast

- Figure 1b: CT scan of chest without contrast

- Figure 1c: CT scan of chest without contrast

- Figure 5. MRI scan of the brain with and without contrast

- Diagnostic Procedure(s) and Result(s)

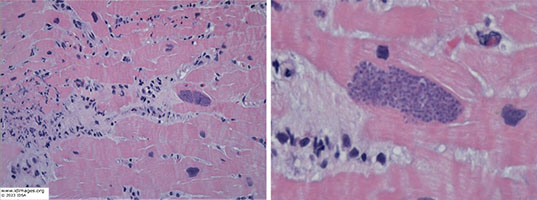

A cardiac biopsy showed Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoites with surrounding inflammation. Serum toxoplasma quantitative PCR was 38,000 copies, although the patient’s toxoplasma IgG negative. Bronchoscopy was grossly normal, with negative bacterial, fungal, and AFB cultures. Other negative BAL studies included PJP immunofluorescence, aspergillus antigen, HSV NAAT, VZV NAAT. CMV NAAT was positive on BAL but negative in blood. Toxoplasma NAAT from BAL fluid was also positive. Lumbar puncture showed 4 WBC/µL (47% lymphocytes, 43% monocytes, glucose 102 mg/dL, protein 87 mg/dL), CSF toxoplasma NAAT positive. CSF bacterial, fungal, and AFB cultures negative.

- Figure 4. Cardiac biopsy with H&E staining

- Treatment and Followup

- Given the diagnosis of disseminated toxoplasmosis and her prior allergy to TMP-SMX, she was transferred to an intensive care unit for desensitization and started on IV TMP-SMX with goal of 10mg/kg total per day, renally adjusted. She developed worsening mental status, oriented only to self, possible seizure like activities in the days following initiation of therapy. Following evaluation by Neurology, she was found to have new onset seizures. Given concern for an immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS)-like response to lysing of toxoplasma, she was started on dexamethasone 2 mg every 4 hours with improvement in mental status, which was weaned to 2 mg every 8 hours after 2 days, and stopped after 2 additional days. Following improvement in mental status, she was changed to oral TMP-SMX which was continued for approximately 12 weeks at which time repeat MRI brain appeared back to prior baseline. She was then transitioned to suppressive TMP-SMX 1 DS tab daily, which will continue indefinitely.

- Discussion

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular parasite with a latent phase that is often asymptomatic in immunocompetent patients but can lead to severe disease in immunocompromised patients, either during primary infection or during reactivation (1).

Disseminated toxoplasmosis can lead to a wide variety of clinical presentations and, in this case, included cerebral abscesses (often visualized as multiple ring enhancing lesions), myocarditis mimicking rejection, pneumonitis (which may resemble pneumocystis on cross-sectional imaging) and likely gastroenteritis (1, 2).

Possible mechanisms of infection in solid-organ transplant (SOT) recipients include graft transmission, reactivation of latent infection, and new exposure (from cat feces or undercooked meat, especially wild game). In this case, it was likely contact with cats. Heart transplant recipients are at a higher risk for donor derived transmission of toxoplasmosis compared to other SOT recipients as the parasite is encysted in muscle; however, given the timeframe and donor/recipient serostatus here, this case is more likely due to new primary infection. As cardiac toxoplasmosis can mimic rejection, misdiagnosis and administration of steroids is a risk for worsening dissemination (1, 3). In immunocompromised patients at high risk of toxoplasmosis (due to positive serostatus in patients with HIV/AIDS or D+/R- in patients who have had a heart transplant), TMP-SMX or pyrimethamine with dapsone and leucovorin are effective in preventing disease (1, 4).

Toxoplasma IgG is often used as an initial screening test for toxoplasmosis, as it has high negative and positive predictive value; however it is less reliable in patients who are immune suppressed, including those with hypogammaglobulinemia or in acute infection prior to seroconversion (5). The toxoplasma IgM antibody is also notable for its poor performance as well, with false positives being common (1, 6). In SOT patients with a high index of suspicion, a negative antibody screen should not be used to rule out disease. Diagnosis may be obtained by histopathology as well as specific NAAT testing on involved tissue, fluid or blood (1, 5, 6).

Although traditionally first line treatment of toxoplasmosis consisted of pyrimethamine with sulfadiazine and folinic acid, given recent drug availability concerns, there is increasing evidence of successful treatment with TMP-SMX, including for CNS disease (4). In the setting of HIV, treatment is typically administered for 6 weeks with secondary prophylaxis continued until the CD4 cell count is >200/microliter for 6 months; however, given slow improvement in our case we elected to treat until radiographic and clinical resolution (12 weeks) and continue secondary prophylaxis indefinitely, given the patient will continue to be immunocompromised.

- Final Diagnosis

- Disseminated toxoplasmosis

- References

-

- Montoya C, Gomez C. Toxoplamosis After Solid Organ Transplant. In: Transplant Infections. Springer International Publishing; 2016. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28797-3

- Hermanns B, Brunn A, Schwarz ER, Sachweh JS, Seipelt I, Schröder JM, Vogel U, Schoendube FA, Buettner R. Fulminant toxoplasmosis in a heart transplant recipient. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197(3):211-5. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00036

PMID:11314787 (PubMed abstract)

- Khurana S, Batra N. Toxoplasmosis in organ transplant recipients: Evaluation, implication, and prevention. In: Tropical Parasitology. Vol 6. Medknow Publications; 2016:123-128. doi:10.4103/2229-5070.190814

- Konstantinovic N, Guegan H, Stäjner T, Belaz S, Robert-Gangneux F. Treatment of toxoplasmosis: Current options and future perspectives. Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2019;15. doi:10.1016/j.fawpar.2019.e00036

PMID:32095610 (PubMed abstract)

- Rajput R, Denniston AK, Murray PI. False Negative Toxoplasma Serology in an Immunocompromised Patient with PCR Positive Ocular Toxoplasmosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26(8). doi:10.1080/09273948.2017.1332769

PMID:28700250 (PubMed abstract)

- Villard O, Cimon B, L’Ollivier C, et al. Serological diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;84(1). doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.09.009

PMID:26458281 (PubMed abstract)

- Notes

- ID Week 2023 - Fellows' Day

Anna Czapar, MD, PhD UChicago Medicine With contributions by: Elizabeth Bell, MD, Huihua Li, MD, PhD, Michael T Czapka, MD

- Citation

- If you refer to this case in a publication, presentation, or teaching resource, we recommend you use the following citation, in addition to citing all specific contributors noted in the case:

Case #23003: Diarrhea, weight loss and fatigue in a heart transplant recipient [Internet]. Partners Infectious Disease Images. Available from: http://www.idimages.org/idreview/case/caseid=607

- Other Resources

-

Healthcare professionals are advised to seek other sources of medical information in addition to this site when making individual patient care decisions, as this site is unable to provide information which can fully address the medical issues of all individuals.

|

|